Shared Code at Quizlet: Deciding on Kotlin Multiplatform

For readers who don’t know about us already, Quizlet’s mission is to help our users practice and master whatever they’re trying to learn. We primarily do this by building tools for learners to create, study, and share content, with more than 50 million students and teachers using our product each month.

In this article, we’ll share the details of:

- How we came to the conclusion that we should invest in shared code

- Different industry approaches to shared code and their limitations

- Lessons we learned from our first attempt at shared code with JavaScript

- Why we decided to rewrite our shared code in Kotlin Multiplatform

Like many startups, Quizlet began as a product for a single platform: the web. Our core product offering was essentially user-generated digital flashcards, and was originally created to master vocabulary.

In order to “assess” a user’s mastery over a specific element, we would simply pick at random from the list a user was studying, ask them to type in the answer, and perform a string equality check between the user’s submission and what the database said the correct answer was. If we were feeling generous, we might ignore case or punctuation.

These were simple times.

As the years progressed, word of Quizlet spread from student to student, teacher to teacher. We were being used by:

- tens of millions of users

- who were creating millions of sets of study material

- which spanned thousands of different subjects

- with demand to be able to study things across several different modalities

Things were starting to get complicated!

Quizlet’s Secret Sauce 🍝

To power the unique use cases for our rapidly growing userbase, we had to go beyond simply querying a database, throwing things into a UI, picking a random element, and using String comparisons to assess correctness.

Quizlet needed to be smarter.

We began writing extremely specialized, domain-specific logic to help our users learn more effectively. Some examples of this kind of business logic include:

- standardized analytics events to help track learning outcomes

- a context-dependent grading rule engine to go beyond simple string comparisons

- modeling the user’s brain to help them retain information better

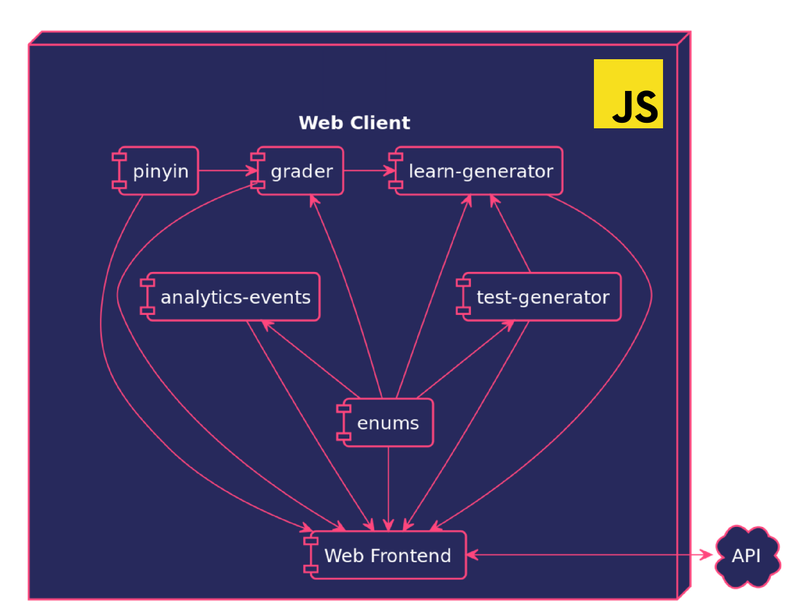

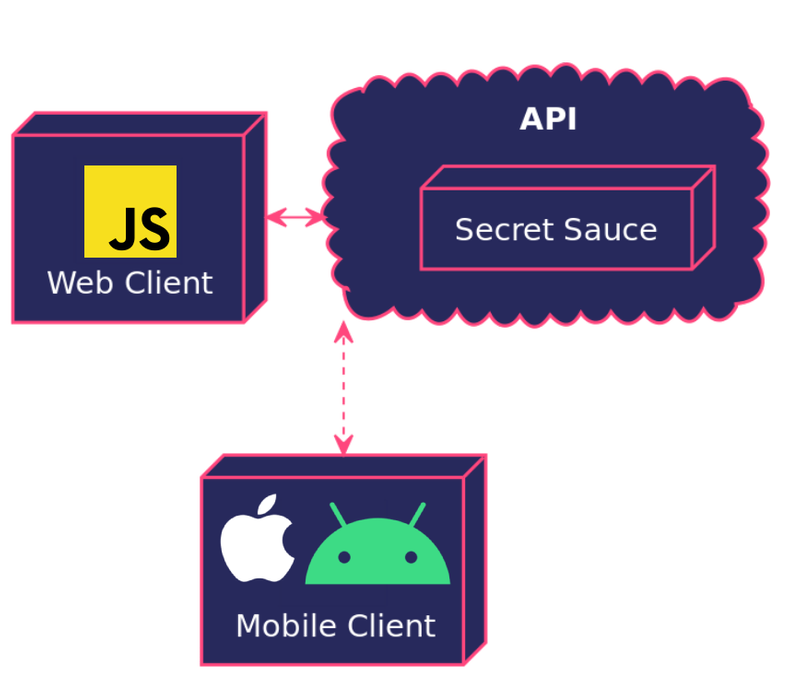

In visual terms, our website went from this:

to this:

Each of these pieces of code are tied to Quizlet’s mission to make education better and more accessible. Each of these components also requires a deep, domain-specific understanding of our specific product and market, well beyond what it takes to write a generic web application.

This category of code is what we will refer to as a business’s “Secret Sauce.”

The Secret Sauce elevates an app from a simple view into a database to a product that delivers delightful experiences and results. The Secret Sauce is directly responsible for both empowering users, and outperforming competitors.

While it’s easy to infer that continued investments in the Secret Sauce have outsized impacts on a product, Quizlet was reaching a phase where that was easier said than done.

The web team had years to implement the fundamentals of the website before finding the need to dive deep into the Secret Sauce. But our fledgling mobile teams were still trying to reach parity on even the most basic features.

It’s hard enough to write niche, complicated, domain-specific business logic and get it right once. Writing it precisely the same on three platforms, where two of them were starting from scratch, and also had to deal with persistence and networking concerns?

This was proving to be a nightmare.

If we wanted to continue to make Quizlet magical, we had to address this problem head-on.

But how?

Stop? 🛑

One option was to declare that parity across clients is impossible with this category of features.

The most literal interpretation of this would mean that we simply wouldn’t support advanced features on our clients. We could just stop rewriting this fancy logic on non-web platforms and cut our losses.

The more likely situation would have been that we moved to an API-side implementation of our secret sauce instead of performing those operations on-device.

For many businesses, requiring internet connectivity for core product features might be a very reasonable requirement! Quizlet however has a particularly strong affinity for mobile users with limited Internet access.

Younger users and learners in developing countries tend to use mobile devices more than desktop computers. These same users also tend to have less reliable access to the Internet, either due to data caps or connectivity issues.

Furthermore, the components of Quizlet’s secret sauce that we would need to move behind the API are all extremely central to the user experience.

If we

- only had to call out to the server once per session,

- could do so in the background without blocking the user from proceeding,

- could cache the result, and also

- gracefully fall back if the server could not be reached…

then maybe waiting a second or two for a response might be fine.

However, our users rely on our Secret Sauce every few seconds to respond to user input during core studying flows. Taking even a second per request over a slow connection would result in an unacceptable user experience. As a result, this wasn’t a trade-off we were able to justify.

Slow Down? 🚧

Another option at our disposal was to slow down the pace at which we were writing advanced features that push the boundaries in learning.

This would give our mobile teams the breathing room to write an implementation of our Secret Sauce for each platform. In this world, we may have also been able to write test cases in some declarative way that all three platforms could validate against.

While taking a breather is always an option, maintaining a high velocity of feature development is what allowed Quizlet to get to where we are today. We understandably didn’t want to feature-freeze our product.

Double Down!

The final option was to invest heavily in our ability to ship such features across platforms and double down on our Secret Sauce. For some companies, this might just mean hiring a ton of Android and iOS engineers to rewrite the secret sauce onto their platforms.

The approach that caught our eye however, was investing in our ability to write domain-specific code once, and share it across platforms.

Cross-platform shared code is far from a novel idea that we came up with at Quizlet. Several other companies have attempted it before us, in many different ways, with varying degrees of success.

Several other companies will do it after us and hopefully learn from our experiences.

Approaches to Shared Code in Industry

Here’s a very, very brief summary of approaches, technologies, and learnings on shared code from various companies.

Share All the Things!

Promise: Write your entire app once and run it everywhere

Industry Examples: React Native at Airbnb, Pinterest, Nextdoor

Realities

- Heavy reliance on bridging infrastructure

- Difficult to seamlessly integrate with existing native apps

- Apps may have performance issues due to differences in threading models

- UI can feel non-native

- Less mature frameworks/libraries than native code

- Difficult to integrate deeply with the OS when you need to do so

Unfortunately, many of the large companies that were pioneering React Native ended up discontinuing their use of it, for both organizational and technical reasons.

Every company that I know of that has tried this hybrid approach has walked it back months later. . . . The companies that seem successful with React Native seem to be the ones that have their entire app in RN and started out the app that way. . . . We’re still in the process of winding down RN here at Nextdoor. — Vivek Karuturi (Nextdoor)

Share Persistence and Networking Things!

Many issues from the previous approach stem from trying to share UI implementation, and from using JavaScript in performance-sensitive environments.

A few companies have tried to side-step these issue by sharing non-UI code. This code may rely on persistence and networking, and is typically written in highly performant languages such as C++.

Promise: Have a native UI and write non-UI code only once

Industry Examples: C++ at Dropbox, Slack, SafetyCulture

Realities:

- Issues with hiring/retention due to niche/custom tooling and languages

- Persistence and networking requires strong concurrency support

- Potential performance overhead with JNI on Android

- Much more difficult to share code with frontend web clients

- Loss of types when crossing the module boundary

- Some functionality simply works differently on different platforms

An industry example of this line of thinking is Dropbox. They wrote shared code for features such as syncing the camera roll on mobile devices, which introduces a dependency on networking and storage access. Dropbox Engineering recently posted about their experiences with shared C++ and announced that they stopped using it.

Although writing code once sounds like a great bargain, the associated overhead . . . outweigh[s] the benefits (which turned out to be smaller than expected anyway). In the end we no longer share mobile code via C++ . . . and instead write code in the platform native languages. —Eyal Guthmann (Dropbox)

Slack also followed up with a similar post, where they announced that they no longer use shared C++. Instead, they have switched gears to invest in engineering processes to maintain consistency across clients.

While we are no longer building a shared library, Slack still needs to maintain consistency and reduce duplication of effort, while developing separate implementations of client infrastructure. — Tracy Stampfli (Slack)

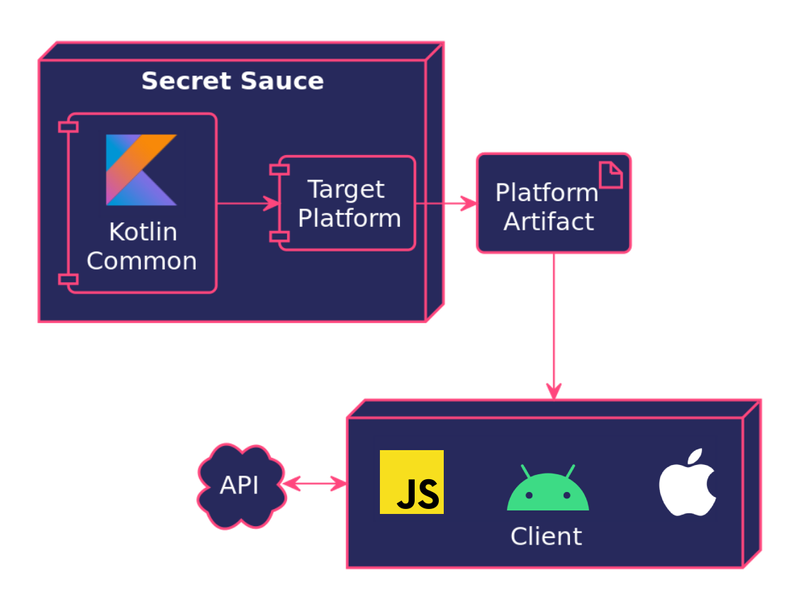

Share the Secret Sauce 🍝?

Common threads with the previously described approaches were the reliance on cross-platform abstractions for UI, persistence, networking, and/or serialization.

These concepts are hard to generalize across multiple platforms. As a result, we posit that frameworks attempting to do so tend to either:

- oversimplify to the point of having to bypass the framework to accomplish key tasks, or

- overcomplicate to the point of being too much of a hassle to work with in a productive manner

It would undeniably be nice if we could write our entire codebase once and share it everywhere. However, any given engineer at Quizlet already knows how to deal with UI, persistence, and networking concepts on their respective platforms.

Knowing ins-and-outs of German grammar rules to maintain grading logic, or keeping up with cognitive science research to model a user’s ability to remember information are much more difficult tasks.

Unlike companies like Airbnb, we had to implement our secret sauce on-device, so we had more pressing demands than iterating quickly on UI.

Unlike companies like Dropbox or Slack, our secret sauce doesn’t rely on the fine-grained details of network or disk I/O.

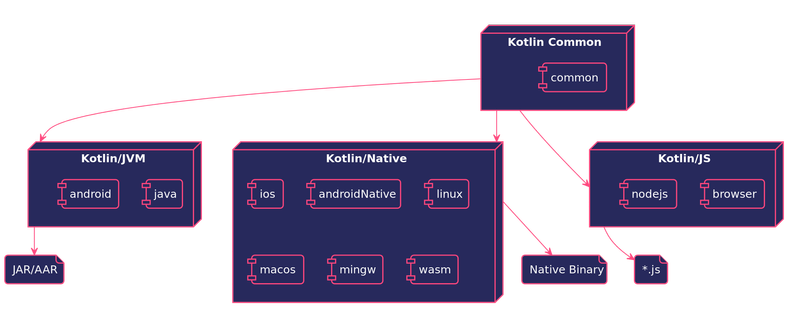

At Quizlet, we had a clear sweet spot at the intersection of our Secret Sauce and the areas where shared code has minimal complications.

So how did we do it?

Attempt 1: Shared JavaScript

Our first attempt to share code was an attempt to reuse what we already had.

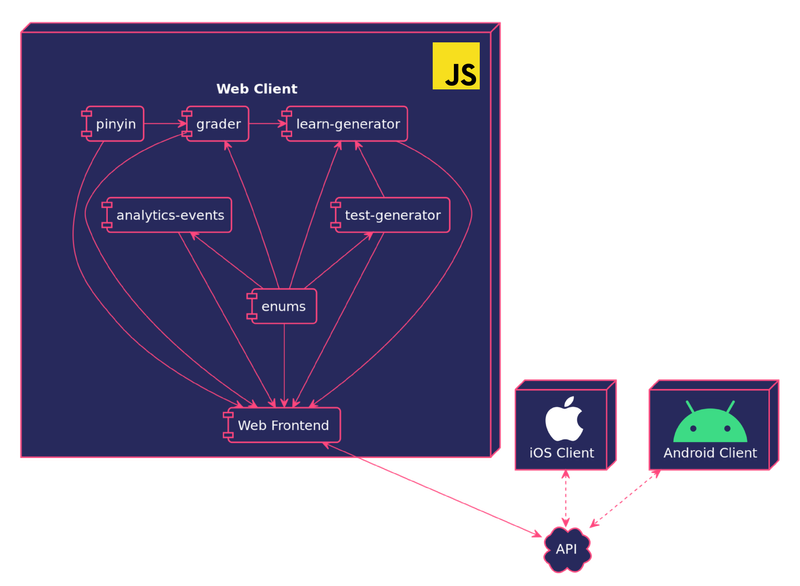

The Quizlet Secret Sauce was originally written in JavaScript to target our web client. The challenge was getting it to run on mobile.

With a bit of initial setup, we were able to clean up the existing web code along our class boundaries and export a suite of small libraries. Each library was responsible for a distinct portion of our Secret Sauce business logic.

We could then bundle these files into our mobile apps and run them. The end-result was to read each library file into a String in-memory and pass it into a JavaScript runtime.

In order to interact with this code, we would marshal “real” iOS or Android classes into JS-friendly versions, and build a string that ran a given function from the JS runtime. We would then marshal the output strings back to “real” classes.

This was relatively straightforward to throw together on iOS using an official Apple framework called JavaScriptCore. JavaScriptCore powers Safari on iOS, is maintained by Apple, and behaves consistently across devices.

Initially, we attempted the same approach on Android using the official WebView::evaluateJavascript API. With this approach, we ran into several issues with performance, stability, and variance across manufacturer implementations. In a blog post from 2016, we detail how we evaluated several external third-party JavaScript engines before deciding on the J2V8 library for Android.

Far from Problem-Free

Our experiences sharing JavaScript on native mobile were shaky.

While web browsers are of course tailor-made to run JavaScript, relying on JavaScriptCore/J2V8 on iOS/Android raised significant issues.

Relying on disk I/O to load the initial JS files, building and retaining a reference to an entire JavaScript context, and then having to marshal “real” objects to/from JavaScript in order to interact with the code resulted in huge performance issues and memory leaks.

Unlike actual native code, interacting with untyped objects that are passed to/from JavaScript contexts was disastrously error-prone, without any compile-time safety.

Since none of the shared code was being run in a first-class mobile runtime, debuggability was also an issue once crashes inevitably occurred.

On Android, the J2V8 library caused our APK size to almost double.

And this is all before even mentioning the almost comical disdain for JavaScript among mobile developers 😱.

All-told, these issues resulted in an ecosystem where frontend web developers might have felt comfortable writing shared code, but mobile developers certainly did not feel comfortable consuming it.

But It Worked

Problems aside, sharing our Secret Sauce through JavaScript worked. For years!

As much fun as people have hating on JavaScript, just getting to this point was an enormous win for Quizlet.

We were able to write our most critical business logic in one place, ship it across multiple platforms, and unblock our resource-constrained native mobile teams. Most importantly, we were able to do this without committing to writing our entire client with the same framework.

Without shared code, we would not have been able to get our award-winning Android and iOS clients to where they are today.

Lessons Learned

Through our experiences with Shared JavaScript, we learned several lessons.

Clean interfaces are crucial.

Writing code with clear interface boundaries made it much easier to extract later. By isolating our vital business logic from regular application code, we were able to share this logic across applications!

Aggressively validate inputs along the public API.

It’s easy for misunderstandings about the meanings of parameters to arise in a complex module. This is doubly true when the module is used by many people who may have never talked directly to each other. Aggressively validating for unexpected input, especially in a loosely-typed language like JavaScript, helps minimize issues due to miscommunication or under-documentation.

Practice Test-Driven Development.

Test Driven Development (TDD) pays extra dividends with shared code. TDD is nearly always a great way to build software, but it is especially well-suited for shared modules with little dependence on external state.

Particularly with shared code, investing in TDD:

- Minimizes time spent debugging the final artifact within a host client, which tends to be more difficult than debugging purely native code.

- Minimizes the number of times we have to have to recompile/repackage shared code for inclusion into a client due to implementation errors. This multi-step processes can be awkward and takes more time than working entirely in a native environment.

- Gives us extra confidence in the shared code we write, preventing issues that have ripple effects across multiple host apps.

Complex state machines and rule engines are ideal candidates.

Compared to user interfaces, persistence, or networking, state machines and rule engines are well-suited for shared code. This isn’t to say networking and persistence are bad candidates for shared code: they just have additional complications to work around.

By focusing our shared code efforts on code based around state management and control flow, we saved our engineering team countless person-hours with minimal time spent on cross-platform threading or concurrency concerns.

Enter Kotlin Multiplatform

Kotlin is a programming language created by JetBrains. It was designed to run in the JVM and has excellent interoperability with Java. Once it took off within the Android development community, it also received backing from Google, through the Kotlin Foundation.

It’s only been getting more popular ever since!

Kotlin Multiplatform was announced at KotlinConf 2017. The basic promise of Kotlin Multiplatform was to bring the same magic of Kotlin’s excellent JVM interop to other runtime targets and platforms.

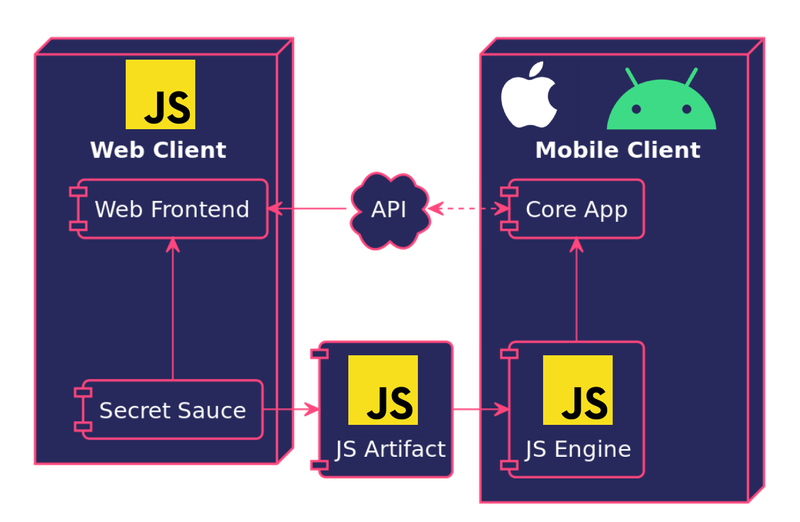

By building out separate compiler backends for different targets, Kotlin Multiplatform compiles platform-agnostic Kotlin code (aka “Common” code) into many different artifacts.

One of the core features of Kotlin Multiplatform is the ability to write platform-specific declarations. This allows Kotlin Common code to define a class or function as expected, and then continue to use it within Common code.

// Common

expect fun platformName(): String

fun getGreeting(): String {

return "Kotlin is running on ${platformName()}!"

}

Each platform-specific sourceset is then required to provide an actual implementation for every expected declaration. The beauty here is that platform-specific sourcesets are not restricted to Kotlin Common. Instead, they are free to use every API available to that platform!

// Android

actual fun platformName(): String = "Android"

// iOS

actual fun platformName(): String {

return UIDevice.currentDevice.systemName() + " " +

UIDevice.currentDevice.systemVersion

}

// JS

actual fun platformName(): String {

return Navigator.userAgent

}

Though it is excellent to see that Kotlin Multiplatform has well-supported networking, persistence, and serialization libraries, none of these were even necessary to support Quizlet’s shared code.

What caught our attention was how Kotlin Multiplatform’s unique approach addresses many of the issues we had with sharing JavaScript across platforms.

Namely:

- performance,

- error-proneness, and

- developer satisfaction.

By generating actual Objective-C Frameworks, JavaScript files, and Java bytecode, Kotlin Multiplatform promises the ability to write code in Kotlin and have it run as a first-class citizen on each platform.

This approach eliminates the most problematic areas of our Shared JavaScript approach: the bridge layer and external runtime requirement. While other technologies (such as shared C++, Rust, or Go) might have foregone the external runtime requirement, the they still rely on bridging technologies.

As mentioned earlier, the shared code interop area traditionally relies on manual type declarations, loss of type-safety, and a considerable performance hit when marshaling between types on mobile clients. Kotlin Multiplatform on the other hand, generates type-safe/null-safe code for our mobile clients. Our Android client can treat Kotlin Multiplatform code the same way it treats all Kotlin code. Our iOS client can safely create instances of Kotlin classes as if they were written in Objective-C.

Furthermore, Kotlin is a modern language, with established tooling, and great IDE support: It is after all, designed by an IDE company!

Quizlet’s Android, iOS, and backend engineers are more eager to write and maintain code written in Kotlin rather than JavaScript. After playing around with the interactive “Kotlin by Example” section on the Kotlin website, even our frontend web engineers found themselves impressed by Kotlin.

Kotlin Multiplatform addresses all of our pain points with Shared JavaScript on mobile clients. In early 2019, Quizlet migrated all of our shared code over to Kotlin Multiplatform, and we are using it in production to serve over 50 million monthly active users.

Was the process perfect and painless? Of course not! Some issues we had to navigate include:

- Increasing Kotlin knowledge across our engineering organization

- Developing workflows to publish, consume, and debug iOS and Web artifacts

- Not having Typescript definitions for JS clients (although JetBrains is working on this!)

- Navigating differences in Kotlin types on JavaScript and iOS when validating inputs

But was it worth it? Yes it was!

In the future, we’ll continue to share more detailed benchmarks and specifics about our experience migrating our shared libraries from JavaScript to Kotlin Multiplatform.

Keep an eye out for future posts!